Join The Poetry Salon’s Writing Classes Here.

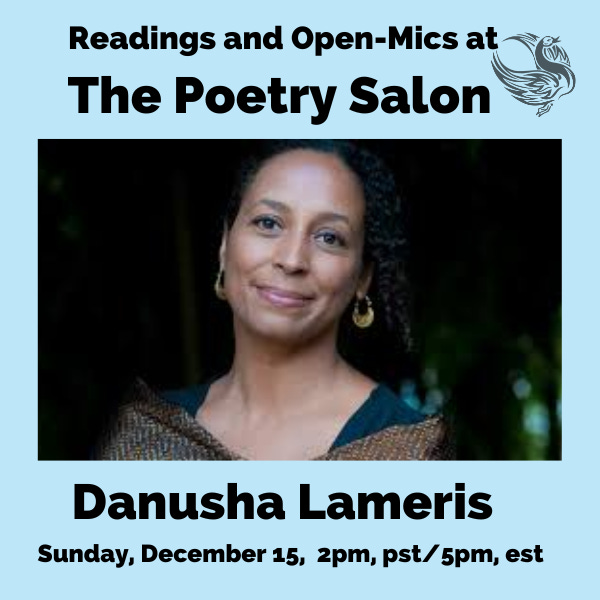

Alphabet of the Apocalypse by Danusha Lameris

Why this poem fascinates me

In my early twenties I taught Ancient History to Jr. High students at a small school in California. I was probably just as intrigued by the subject matter as any of my students. I loved learning about ancient people, the art they made, the things they discovered, the way they moved civilization forward with tools that we would consider primitive by today’s standards.

Even after I stopped teaching the topic, I continued to read up about ancient cultures, the discovery of old sites and statues. Later, when I moved to Costa Rica and had more free time to both read and walk under streets lined with mango trees, I realized that a lot of my fascination with older cultures was really my fascination with nature. I was curious how earlier societies put nature and animals and plants at the center of their lives, in their iconography, in their texts and poems and prayers. Although I like modern living in many ways, I worry that most people have lost touch with the natural world, and not only is that robbing all of us of an appreciation for our planet, but it’s also putting the planet in danger.

I’m not alone in my concern. Many worry that as we get farther away from our understanding and connection to nature, the closer we come to destroying it, and also ourselves in the process.

When I read this poem by Danusha Lameris, in her book, Blade by Blade, I thought, here’s a poem that gives voice to all of these concerns, in one eloquent poem. Here is the poem by Danusha Lameris.

Alphabet of the Apocalypse Where does an end begin? Why not with A— Atlantis sinking back into the sea with its aquatic spires and crystal architecture. B for herds of bison whittled down to almost nothing, drinking from the drying lake. I don’t know when the body’s cells decide to give up the ghost. How they start to catapult toward decay. Death knell of the form, its sweet and terrible diminishment. First decrease, then end. Snowy egrets, standing in a glade. Eagles, elephants, elk. The late pink light through groves of eucalyptus. Great green planet, formerly known as Earth—Will you end in fire? What will they call you when we’re gone? Who will be left to sit beneath the moon’s nightly glow? Who will recall the glaciers’ tall blue countenance? Here on Earth as it is in Heaven. But isn’t heaven a white expanse of nothing capped with nothing? So much for the ibex, its long-pronged horns. So much for Italy, iguanas, the iris, the color indigo, steeped in vats in rural India. So much for June, month of brides clasping cut flowers—orange blossoms, jasmine, coral-colored roses—in their careful hands. I’ve never been to Kansas or seen a kangaroo, though once a katydid hid in my curtain, and sang, all night, its little virgin song. O Lamb, O Lion, it matters little now whether you lie together, on the bare and ruined soil. Mother, mountain, mammary. No more, these founts for mammals and mystics. It was never enough: nectar from the orchard, nightingales singing from the highest boughs. Narwhals decorating the northern seas. Once, I took a child to the ocean for the first time. I can’t forget the sound she made, that gasp—her mouth an O. Wouldn’t it be better if we’d all stayed pagan, stunned each night at the moon, the trembling stars. If we quivered, still, at the unlikely grass, the song in the river, the shimmer on the face of cut stone. What if we remembered the shy soul in everything—the world shot through with whistle and hum. If we sought, above all, the silence between blades of green, the pause inside the cricket’s choir. To touch the tender core of Things, and tell of it. Pure pleasure. What more could we want? To undress the world, get close to its shiver, rock and spore, river and bark, the dandelion’s naked stem. Our vagabond planet, traveling the galaxy’s milky arm, pulled by forces we can’t see— with us: wanderers, wanters, those who crave. Always restless for the next and next. Following the x-axis of some trajectory we can’t know. To be or not? Which brings me here to the window, looking out at the acacia, blooming acid yellow in the field beside my house. This moment, the zillionth, in a long parade. A something arising from nothing. Existing. And sinking back, again.

A Loose Form of the Abcaderian

Let’s talk about the form of this poem first. Some of you know the term Abacaderian. This is a type of poem where the first letter of each line begins with the letters of the alphabet. This is a kind of deconstructed Abacaderian, which the speaker references in the title, “Alphabet of the Apocalypse.”

The form of this poem really fits the themes. Think about what an alphabet is. It’s 26 letters that make up all of the words in the English language, and so these small pieces make up almost the entirety of creation.

Because this poem is discussing the entire planet, and what might happen to it, it requires a form that is expansive. The speaker of this poem is trying to acknowledge all the parts of the planet and to expound upon how much we have to lose if we lose the plants and animals and all the smaller elements that make up the whole of our Earth home.

Drawing us in by using questions

Part of what works for this poem is the use of questions. The speaker does not pretend they know what will happen to the earth. They aren’t prophesying. They are instead engaging the readers in speculating on what could happen or what is happening. To ask that question, “How does an end begin” she invites us to think about this for ourselves. How would we recognize the beginning of an end? Are we already in the middle of an ending?

She’s making something large and abstract, something that has political and social implications, a lot more personal.

In letters A - J, she lists elements of the natural world, the Bison, the Glaciers, “Eagles, elephants and elk,” etc. Then when she gets to K, “I’ve never been to Kansas or seen a Kangaroo. But I have held a Katydid…” Now she personalizes the concept of the apocalypse. She’s discussing her own relationship to the natural world, what she hasn’t seen, and what she has seen and how it has touched her. The Katydid is so small but it sings this song she calls “virginal.”

I would say the same of the letter “O” where she says…

Once I took a child to the ocean for the first time. I can’t forget that sound she made, that gasp, her mouth an O. This personal annecdote demonstrates the power of nature to entrance the human mind and even the body.

Then we get another question.

“Wouldn’t it be better if we’d all stayed Pagan?”

This reminds me of a poem by William Wordsworth - a sonnet, called “The World is too much with us.” In it he laments that we’re losing our connection with nature and says he would rather be a pagan. This was back in the 1800’s, just at the beginning of industrialization. The word “pagan” usually refers to people who believe in many gods, and in most pagan cultures those gods are related to the forces of the natural world. In both poems I think the poets use the term to mean that we should treat the natural world with reverence and respect. To seek “the silence between blades of green,” to “touch the tender core of things, and tell of it.” This reminds me of the famous Mary Oliver quote. “Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.”

Here I think she begins to speculate not on what is, but what could be. She switches from a warning to maybe a suggestion for how we could do things differently. The poem asks us to consider a different set of values, one where we put the natural world first and come to know ourselves as part of that world. She says if we do this, “What more could we want?”

Further complicating the topic

When we get to the W’s of the alphabet, the speaker calls human beings wanderers, wanters, and notes that we are a restless species always going after something new. However, we don’t know what that newness will bring or where it will lead us.

This describes the way human beings are personally and as civilizations. We are always changing, looking for something new, though we don’t quite know why we do this. And we don’t quite know what the results of this restlessness will be. It might even bring us to extinction.

Coming to peace with a potential apocalypse

In the poem, it brings the speaker to the window, where she looks out at the acacia, yellow as acid. I think that choice is telling. This flower, an emblem of beauty and life, is the color of something that can dissolve life itself. The speaker of the poem says that this moment is one of a Zillion in a long parade of things that rise and then sink back again into nothing.

I believe the end of this poem comes to some peace with the idea that we might all sink back into nothing again, and that the planet, though beautiful, might eventually go extinct.

Register for our reading with Danusha Lameris right here right now!

And Join us For These Other Upcoming Workshops Below.

Paid subscribers will see the link to register at the bottom of this post.

Submitting Poetry Can be Fun!

Believe it or not, you can get work published and have fun doing it. The trick is to do it with a group of friends. Together we will offer practical and moral support, suggestions for where to submit, and tips for how to get your work out there.

Don’t just make fans, make real friends.

Learn to promote your poetry online and offline. Find your ideal readers, get reviews of your work, learn how to organize a book tour, get support from those who have been there before. Have fun doing it!

Do you have a book out but no idea how to market it?

In this event, Jeannine Hall Gailey, author at BOA, will offer insights and useful tips on how to promote your book even if you are an introvert, have no experience with marketing, or are short on time.

We will follow up with a Q&A session where Jeannine will answer individual questions, and help you discover the marketing strategies that are right for you.

Incredible article!

Incidentally, I think Costa Rica is doing a great job of showing how a modern country can still prioritize the enjoyment and protection of the natural world.