Want to join a vibrant community of artists who support your work? Join The Poetry Salon’s writing community here.

Self-Portrait with Bee Sting

Intro

Years ago I heard the singer Regina Spektor sing “I have a perfect body ‘cause my eyelashes catch my sweat” (from her song, “Folding Chair.”) I’ve been thinking about this line for a long time. Usually we think of a body being perfect because it has a particular form. It’s aesthetically ideal. But Spektor’s song says that it’s perfect because of the way it functions.

When you think about it, your body does so many amazing things. it can eat and digest food. It can propel you forward. After you get injured, your body can heal.

The same can be said of the human heart or psyche. After an emotional hurt it can feel like the pain will go on forever, but in the same way a body can heal after injury, the psyche can heal too.

Today’s poem speaks to that subject.

Self Portrait with Bee Sting Last night while watering the garden I mistakenly elbowed a yellow jacket or perhaps a carpenter bee casually bathing in a galaxy of purple aster. And then, as if taking the Circle Train home, we accordioned together vaudeville-style— our physical margins shaken by the brokenness of surprise. Through the torn cloth of my hip pocket, I feel the stinger insert until he stumbles, slow motion, into the flowerpot; inert like a lover who has overexerted himself, then lies down in the husk of a late July night. Now all I have left of him is a raised scar, burning like a silver dollar, and swiftly seen-to with wet tea bags and copper pennies— the way we try to exorcise toxins from our lives: a blue basin next to the crib of a sick infant or a vacuum cleaner hanging in the guest room closet. When he left I didn’t recognize myself in the drapes. I took down the mirrors from the walls, subsisting only on wildflowers and the machinery of my heartbeat which came as a continuous surprise— the new knowledge that my body could outlast death— might heal this deep, sharp, sting.

The literal becomes metaphorical

I often say this in workshop, when you put something in a poem, even if you are describing a literal event, it becomes metaphorical. The reader might think of it as emblematic of something deeper.

This poem appears in Susan Rich’s book Blue Atlas, which centers around an abortion that the speaker of the poems had thirty years earlier. When I spoke with Susan on the podcast she said that originally this poem was titled “Self Portrait with Abortion and Beesting.” Even though the speaker doesn’t put it in the title or say it directly, I could tell that this poem was about more than just a beesting. The sting is a metaphor for other emotional hurts, the hurt of a losing a relationship, being coerced into an abortion, and about other hurts the speaker may not even be able to name.

From event to deeper meaning

At firs the speaker describes the literal event. She uses imagery to bring to life the story of what happened in the purely physical, objective world.

The bee is bathing in a “galaxy of purple aster” when she accidentally elbows it. They accordion and then they seperate. But here the poem becomes about something else.

“We’re both shaken / by the brokenness of surprise.” This is about more than a woman encountering a bee or wasp. The phrase is about all surprises. It’s strange wording makes me wonder, are we broken by surprise? is a surprise just anything that breaks us? It’s an odd and intriguing way of describing the encounter and it elevates the experience from a singular instance in the garden to a more general meditation on life.

The speaker compares the bee to a lover, which is significant. Once he “lies down in the late July night” all she has left of him is a “raised scar, burning like a silver dollar.”

If we look at this as an emblem of a human relationship, then the raised scar is symbolic of many things. The lingering love, the anger, the hurt, and in this case, the unborn child, “burning like a silver dollar. Seen to with wet tea bags and copper pennies./ the way we try to exorcise toxins.”

Notice the subtle shift here from “I” to “we.” The speaker is telling us that she’s speaking here, not just about herself, but about something that applies to all people. Whenever we get a hurt we try to heal it by removing the substance that is hurting us.

She gives the examples of using tea bags and pennies to try to sooth the wound of the sting, but then she gives other examples, the basin next to the crib and the vaccuum in the guest room. Those two items, a crib and a vaccuum, though used separately, evoke the idea of an abortion. In this way she’s subtly nodding to the themes that she’s brought up earlier in the collection.

Making the metaphor clear

Next she says that when he left she couldn’t recognize herself anymore, and so she takes down the mirrors. This is another way of trying to remove what pains her. Yet, in spite of her own confusion, her body continues to work. Her heart beats, even though this surprises her.

Again, we come back to the body. The body goes on automatically. The heart keeps beating. The body begins to heal. This is what the speaker of the poem discovers - that her body can outlast death - and I think this refers to the death of the child, but also the death of the bee, the death of the relationship, maybe even the death of an old version of herself. By continuing to survive, continuing to let the heart beat, the speaker is able to wait out the injury, and, though it surprises her, she is able to heal.

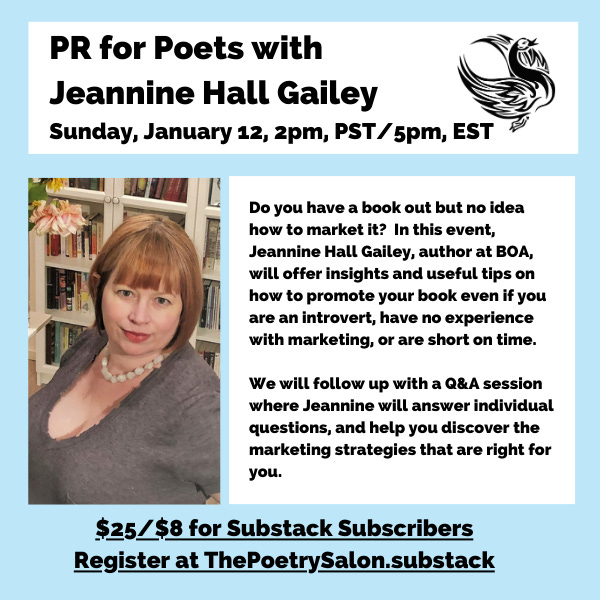

Plus, check out these upcoming events below.

Paid subscribers will see the link to all paid events below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Poetry Salon with Tresha Faye Haefner and Friends to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.